Last Updated on June 9, 2020

In “Emma.” (2020), costume designer Alexandra Byrne has made a love letter to the Austen era. Virtually every garment is historically accurate to the Regency period.

To help keep this site running: Willow and Thatch may receive a commission when you click on any of the links on our site and make a purchase after doing so.

Now that “Emma.” is available to stream at home, we thought it would be helpful to take an in-depth look at the delightful costumes from Byrne, who previously showcased her Regency designs in Persuasion (1996). Subconsciously, we all take in some of a designer’s intent. A deeper look at the choices can shed light on the film’s nuances and make watching more fun.

Below, Alden O’Brien, Curator of Costume and Textiles at the DAR Museum in Washington DC, shows us how the costumes and characters in “Emma.” are informed by the past.

Costume dramas use period dress to set the tone to the director’s vision, create a mood, and delineate characters. Clothing design choices tell you about individual characters’ personalities, and place them in society and their community.

Alexandra Byrne’s thoughtful choice of various Regency era garments and textiles give us a better grasp of each character’s role in the story.

Several designs, such as Emma’s pale pink spencer jacket, are copies of extant garments. The spencer, essentially a short jacket, was initially a brief menswear fad of the 1790s. It quickly became exclusively feminine. Though technically outerwear, many extant spencers are very lightweight and provide little warmth, suggesting they were largely used for varying the look and adding color to the endless white cotton dresses popular throughout the first quarter of the century.

The cording and sleeve details on Emma’s spencer (above) are taken from a circa 1817 garment in the Chertsey Museum collection; the original’s collar has been simplified.

Emma (Anya Taylor-Joy) wears a total of five spencers and at least four pelisses in the course of the movie. As the richest woman in Highbury, Emma would have a generous clothing allowance. If she ordered one spencer and pelisse (fitted coat) each spring and fall, and wore each for two years, this rather extensive outerwear inventory makes sense.

The introduction of the fashionable pelisse was made possible by the new slender Empire-period silhouette; fuller 18th century skirts only permitted unfitted cloaks and short mantles.

In the period drama, we see Emma in her bedroom during a fitting for a pelisse; we see the finished garment, complete with fur trim, in a later scene.

Emma’s pelisses contrast with the clothing of Harriet Smith (Mia Goth) and her schoolmates who wear red “cardinal” or “riding hood” cloaks (yes, they were really called that, and they were a standard of country outerwear).

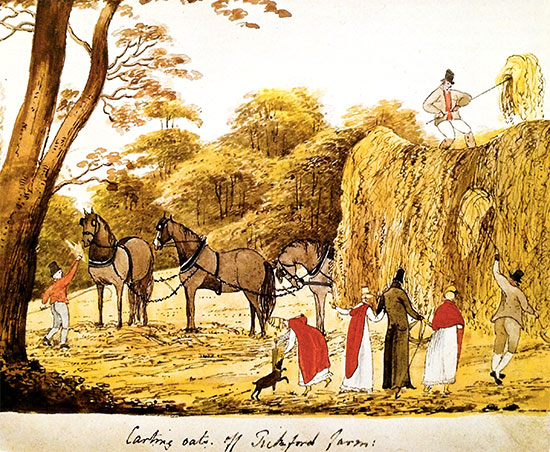

A lovely shot of the students, all in red cloaks, marching briskly along the village’s street could be a scene taken straight out of Diana Sperling’s watercolors in the book Mrs. Hurst Dancing and Other Scenes of Regency Life. Sperling was a young woman of Austen’s approximate class and time, living about as far from London as Austen did in Chawton, and the subjects of her watercolors dress as we can surmise Austen’s family and characters did.

Putting Harriet in a cloak and Emma in a fitted, stylish pelisse makes a visual statement about the relative sophistication of the two characters.

Cloaks were typical in the 18th century but by 1816 were no longer seen among the fashionable set in the city; the red cloak is on the verge of being a marker of a lower, and rural, class. At this stage, it’s still found in a landed gentry woman’s wardrobe, as seen in Sperling’s scenes.

The 1995 productions of “Pride and Prejudice,” and Byrne’s own designs for “Persuasion,” include red cloaks on Lydia, Kitty, and the Musgrove girls. But the one-size-fits-all readymade circular cloak, unchanged in style over decades, is nowhere near as chic as a fitted pelisse whose style changes with each season and must be fitted by a skilled dressmaker. See the many lines of stay-stitching on Emma’s pelisse in the fitting scene, for example.

Over the course of the movie, Harriet’s style improves and she is seen wearing pelisses. She even dons an embroidered net dress over a silk slip to wear to the ball. Machine-made net was a recent technological development, and was quite costly.

We can surmise that either Emma is passing her friend some hand-me-downs, or is advising Harriet on fabric choices when they shop at Ford’s. Several scenes are set inside the store which nearly replicates period images of such shops, but the set designers’ creative touches reminiscent of wedding cakes and candy boxes make it a feminine paradise.

Throughout the period drama, we are treated to visually pleasing dresses. The production’s overall palette is pastel, as if the mood board started with a box of macarons. The iconic white muslins of the Regency are everywhere, as are, to a lesser degree than some Austen adaptations, small-scale printed cottons.

Emma, Harriet, and Jane Fairfax (Amber Anderson), as the younger generation, wear mostly white, often over a colored slip or underdress (called a petticoat at the time — one of several uses of that term). Bryne frequently places colored silk slips under the white muslins, a trend that was probably more widely practiced than recorded in fashion plates. In this scene pictured below, Harriet is in white, and Emma has a colored slip under her muslin.

The colored linings make the hem embellishments that were so emblematic of late 1810s fashions more visible. And one of the pleasures of this production is that it features enough long shots that we get a good look at the hem decorations.

The ball scene at the Crown shows a variety of beautiful hem treatments: flowers and pleats and swags, which closely recall the guests at the ball in Rolinda Sharples’ 1817 painting The Cloakroom, Clifton Assembly Rooms. Below is a close-up of some of the leaf and flower detailing on Emma’s sheer ball gown.

At another evening event, Emma wears what is arguably the most swoon-worthy garment of the entire production: a close copy of the circa 1810 red silk net gown in the Victoria and Albert museum. We see her arrive at the party and are treated to long shots as well as closeups of the embroidery, all copied from the original.

By 1810, brightly coloured and embroidered silks were as popular as white cotton and muslin for women’s evening dresses. John Heathcote’s bobbinet machine, patented in 1809, enabled fine net to be easily produced in wide widths for dresses, which could be hand-embroidered to achieve individual and attractive effects. Net dresses were worn with underdresses of plain silk, sometimes white, or in a matching colour. – V&A

In this behind-the scenes moment (below), Mrs. Elton (Tanya Reynolds) wears a short-sleeved spencer — a nice use of a less common but period garment — and a dress over a yellow slip.

Jane Fairfax (above left, and below) wears a dress without expensive embroidery; Byrne may be suggesting that Jane could not afford the more expensive “work’d muslins.”

In one of the movie posters, Harriet is wearing a dress with elaborate embroidery at the hem, which might be attributable to a generous dress allowance from her father, or might be a gift from Emma.

This dress, and several other of the white muslins in the film, look as if Byrne incorporated antique pieces of fabric in her costumes. While we can’t be certain of this, it’s a common practice in period dramas, especially for the exquisite embroidered or otherwise embellished fabrics no longer being produced. “Titanic,” “Downton Abbey,” and others have used either antique dresses, or scraps of fabric incorporated into new designs.

Ruffles abound in this period, and Byrne makes the most of them. Chemisettes (we would call them dickies) with collars or ruffles which evoked Elizabethan ruffs, were widely used to cover the bare neck. The height of the neoclassical style passed after 1810, and its revealing and clingy styles were made more moderate. In the daytime, bare necks were filled in with chemisettes, and short sleeves were replaced by long, or mitigated with undersleeves or net mitts, like those worn by Emma and others in some scenes.

A jacket worn above the bodice, (with holes for the arms and more finished at the sides and bottom), was a “canezou.” Emma wears one over her dress in the very first scene and several times afterwards, a lovely use of a rarely-seen Regency-era garment. This German portrait showing a canezou worn by the artist’s foster daughter, 1802, is by Friedrich Carl Gröger.

Miss Bates (below, played delightfully by the wonderful Miranda Hart) is the ruffle queen, wearing a symphony of ruffles and flourishes around her neck and on her caps (the latter a required accessory for a spinster). She has probably saved lengths of trim for years, moving them from one garment to another. They represent her determination to maintain standards of gentility.

The floofy effect is also perfectly in keeping with her ditsy conversational style. She wears mostly printed cottons with a dark ground — a good choice for an older lady on a budget, as dark colors are more mature as well as showing less dirt and wear. Her dress is similar to the print on an extant gown in the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia (below), which was part of their 2009 exhibit Persuasion: Fashion in the Age of Jane Austen.

There are few costumes that depart from historical accuracy. When they do appear, it’s not always evident why. In her first visit to Emma, Harriet wears a red knitted spencer (below).

Knitwear was simply not part of Regency fashion, nowhere, nohow, no matter what the period-evoking knitting pattern magazines want to suggest. The very cute crocheted jacket she wears in a later scene (below) also has no place in 1816 Highbury. It’s reused from the period drama Bright Star (2009) about the romance between English poet John Keats and his muse. It was wrong then too.

So is the neck ruffle worn by Emma unattached to a chemisette, which did not exist in the period. Mrs. Elton’s apparently orphaned ruffle (below) is actually, if you look very carefully, a sheer orange organdy chemisette (and undersleeves with wrist ruffle): the outline of the organdy is just barely visible above her shoulder. Orange would not be used here, but it’s perfect for her character: too loud in a pastel world, and silk, too ostentatious for country daywear. She’s also sporting an outlandish hairstyle that comes from the 1830s, but it deserves a pass for its wonderful craziness.

Though we don’t see them, the underpinnings worn by Miss Bates, raise some questions. To be period accurate, they would have stays of either transitional style (18th century structure but shorter and perhaps with cups for breasts), or newer softer corsetry — either would lift the breasts to the right level for this period.

There’s no knowing just what kind of corset or stays they’ve put on Miranda Hart, but it has not done its job of putting the bust where it ought to be at this period. Sometimes actors have individual issues or requirements regarding their costume, and perhaps Hart requested or needed special dispensation in this regard.

Overall, however, the costumes delight at every turn. The attention to detail, down to the accessories, is scrumptious. Every bonnet is made of a different intricate straw and some, like the one pictured below, have net linings.

We see quite a few delicious knitted purses or “reticules,” some of which seem based on extant ones. Emma accessorizes her yellow pelisse with a reticule very similar to the pineapple reticule in the Kyoto Costume Institute collection; another reticule in the period drama has a quirky shape similar to the one at the Metropolitan Museum (below).

The menswear is nicely done too, though an expert in historical men’s clothing could take issue with some of the subtleties (the coat collars lie too flat!). Breeches are better-fitting than in many Austen adaptations as they outline the male leg as they would have in the era.

Frank Churchhill (Callum Turner) and Mr. Knightley (Johnny Flynn) have subtly different styles: the poster (above) reveals Frank in flashy waistcoats (wearing two was a slightly dandified style) and Hussar boots, while Mr. Knightley wears riding boots and a heathered wool coat — the perfect country gentleman.

Men’s collars are high and starched in the film. Too many adaptations fail at using this historical detail, even in an exaggerated way as is done here. They may be a tad higher than, for example, a man like Mr. Knightley would have actually worn, but they fall within acceptable bounds of creative license for dramatic purposes.

The high collars of this period were part of the gentleman’s emphasis on “clean linen and plenty of it,” as the era’s fashion arbiter Beau Brummell prescribed. This French portrait by François-Édouard Picot of Nicolas-Pierre. Tiolier (above) dated 1817 shows a collar just slightly lower than what we see on the men in the movie.

Surprisingly, Mr. Woodhouse (Bill Nighy) is the most fashion-forward man, wearing Cossack trousers with straps under his shoes. These were inspired by the trousers worn by the Russian soldiers who came to England with the Czar during the celebrations of the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Though his natural conservatism would suggest Mr. Woodhouse would stick with old-fashioned breeches as seen in other adaptations of the novel, Nighy’s more vigorous portrayal makes the choice of trousers convincing.

At home we see him in a fabulous printed banyan with matching waistcoat: a perfectly elegant at-home ensemble for the Regency gentleman. Banyans were originally loose gowns made of Indian printed cottons, taken from Indian dress. In the 18th and early 19th century they were at-home wear similar to the later smoking jacket, and were often made like Mr. Woodhouse’s, closer to the cut of a regular coat but somewhat looser for comfort.

Throughout the movie, Alexandra Byrne delights us with a symphony of garments whose frothy beauty and beautiful details belie the deep knowledge of the period she brings to the project.

Byrne’s intimate understanding of the many garments, and the subtleties of their use, give the costumes a richness and depth of meaning. Of all the Jane Austen adaptations to date, they are arguably the finest.

Alden O’Brien is Curator of Costume and Textiles at the DAR Museum in Washington DC. She specializes in the Regency/Federal era and has often lectured on historic costume in films. You’ll find her at The Curator’s Curio: Historic Clothing, Real and in Films. Her exhibition of fashion in America during Jane Austen’s era is online at agreeabletyrant.dar.org/

If you enjoyed this post, wander over to The Period Films List. You’ll especially like the Best Period Dramas: Regency Era List, Recreating the Regency Ball, Block Printed Cottons in the Georgian Era, and our look at the Costumes in Pride and Prejudice.

Shay

February 24, 2021 at 10:02 pm (4 years ago)wWll I went down a rabbit hole going to the exhibit at the DAR museum, after reading this fascinating article. The best thing about the latest Emma movie was (in my opinion) the costumes which I thought were stunning. Loved the critique.

Ruth Thornhill

December 1, 2020 at 7:31 pm (4 years ago)Loved this about the fashion. Although I’m looking for a hair piece like Mrs. Bates wears when greeting someone while she is in bed?

I thought it was in this adaptation of Emma.

Do you have any leads?

Sincerely, Ruth

Nancy Mayer

June 9, 2020 at 6:07 pm (4 years ago)Thanks ,Alden. AS usual the clothes are lovely to look at. I haven’t seen the film but have read several review and comments about the movie. The majority of the blogs and reviews I have read have discussed the clothes. Elsewhere I have said that I think Harriet is dressed too finely for her status .

k

October 18, 2022 at 6:00 am (2 years ago)although that would be an in period truth, the wealthy tradesmen, and their children, but legal and natural, dress above their station because they have the funds for it.

Katherine D.

June 7, 2020 at 9:42 am (4 years ago)Just watched the movie yesterday and was fascinated by the beautiful garments in it. Thank you very much for this informative post!

Janeth Patricia Cienfuegos Hernandez

May 20, 2020 at 5:43 pm (5 years ago)Fabuloso. Me encanta encontrar un análisis tan detallado respecto al vestuario en la película; además, incluir también unos párrafos para la que fue la moda masculina. Gracias por este post.

Lauren

May 7, 2020 at 1:27 pm (5 years ago)You take no issue with the white dress in the first 15 minutes of the film, that has many strips of rickrack trim all over it? As far as I know it wasn’t around until 1860.

Debra Matheney

April 6, 2020 at 1:13 pm (5 years ago)Lovely post. Thank you, Ms O’Brien, for including the male fashions as well.

Janis

April 5, 2020 at 12:03 am (5 years ago)I just love reading every word here, so informative, interesting and well written, thank you