A mordant (the fixing agent) on a textile bonds the color to the areas that receive the dye, and has the benefit of producing powerful tones that do not fade. Some dyestuffs don’t need a mordant, but madder does. In the resist method, parts of the fabric are protected from the dye by being first covered with a paste, like wax.

Gujarat, and later Rajasthan, first excelled in India in the traditional method of relief printmaking, the block print. Block printing most likely originated in Persia or Egypt, but it was in India where the technique was perfected.

A raised surface design is created by cutting away the negative space on a block of wood, and the face of the block is inked and stamped by hand onto fabric, with precision and repetition to form the pattern. Both woodblock and copperplate printing are called direct printing methods, because the color is transferred directly to the cloth. As we will see below, Europe (with centers in France and England) later adopted the technique to print on calicos, wools and linens.

The use of wooden blocks to print or stamp designs on cloth, especially cotton, is still quite common in India, though by no means so general as in former years. The designs used vary considerably from place to place, but the method is much the same everywhere. The designs are first drawn on paper, which is pasted on blocks of wood. The wood is then cut with a crude engraving tool to the depth of about one-third of an inch. Holes are often cut through the block to allow the air to escape from the cavities formed by cutting out the design. This allows the dye to penetrate all the parts without danger of air bubbles. The wood used must be firm and fine grained. Different woods are used in different parts of India. Teak and ebony, though not the ones most commonly used, are said to be preferred in certain regions. – Block Prints from India for Textiles

Commonly used woods include the sycamore, plane or pear, and the block must be several inches thick to prevent warping, and be entirely flat, so as to receive the transfer of the reverse image before being cut. A block is created for every color in the design.

To achieve the desired print, the mordant, resist, painting and relief methods might be employed on one textile. The terminology used for the methods of block printing can be confusing and depend on who is describing or categorizing the textiles. For a fuller explanation, see this article on resist and mordant dyeing.

In 1600, Elizabeth I gave the East India Company a monopoly on trade between England and the Far East. The Dutch, French and Danish also formed similar companies. During the 17th century the East India Company shipped relatively small quantities of textile goods to England. But India was to become the greatest exporter of textiles the world had ever known, with the trade reaching its height in the 18th and 19th centuries. Bullion was sent to India to trade for printed textiles, which were then shipped to Indonesia. A large proportion of the fabric would then be traded for spices, which were sold with the remaining textiles in London for bullion, so the three-way trading trips could start all over again. Lengths of patterned silk, cotton, and cotton and silk mixtures, handkerchiefs, neck-scarves and table napkins were shipped in their thousands to England. – V&A

Working class women of Marseille, France were wearing cottons in the 17th century, and were among the first to wear the block-printed fabrics. The first recorded manufacture of block-printed Indiennes in France was in Marseilles in 1656. (When cotton Indian cloth reached the UK and America, whether it was printed or not, it was generally called calico, and when printed, it was called chintz. In France, the same fabrics were known as Indiennes.)

In the 1660s, the painted and printed cottons from India were popular in Paris at the court of Louis XIV, for whom designs could be adapted to taste. It would soon follow that the strong, colorfast prints became fashionable with more layers of French society.

Women with coquettish airs were imposing in robes à la française and robes à l’anglaise throughout the period between 1720 and 1780. The robe à la française was derived from the loose negligee sacque dress of the earlier part of the century, which was pleated from the shoulders at the front at the back. The silhouette, composed of a funnel-shaped bust feeding into wide rectangular skirts, was inspired by Spanish designs of the previous century and allowed for expansive amounts of textiles with delicate Rococo curvilinear decoration. The wide skirts, which were often open at the front to expose a highly decorated underskirt, were supported by panniers created from padding and hoops of different materials such as cane, baleen or metal. The robes à la française are renowned for the beauty of their textiles, the cut of the back employing box pleats and skirt decorations, known as robings, which showed endless imagination and variety. – The Met

Below is a stunning Robe à la française, circa 1770 in the LACMA Costume and Textiles Collection. The French dress is made from a block-printed and dye-painted plain weave cotton, with silk passementerie.

Chintz, related to a Sanskrit word meaning coloured or spotted, now means a cotton or linen furnishing fabric of floral pattern stained with fast colours and made anywhere, but it originally referred only to colour-fast, light, cotton fabrics made in India for the English market. Chintz production was a very complex process involving painting, mordanting (fixing a dye), resisting and dyeing depending on the colour being used. Different colours required different processes. The original chintz designs were hand-painted and resist-dyed but block-printed designs were incorporated later. Goods were listed by importers as painted, regardless of whether they were painted or printed. – V&A

The area of Surat, India became a center for export of painted and hand printed calicos and chintzes, which rapidly gained popularity throughout the West. The even weave of fine cotton muslin and its ease of accepting dye made it an ideal medium for printing, and its lightweight breathability, natural look and ability to drape made it a quick favorite for dresses among European women.

The circa 1740 – 1760 Georgian British dress below is on display in the National Museum Of Scotland: Woman’s dress, in white cotton block-printed and painted in black, red and purple-blue with a pattern of broad stripes alternately filled with a repeating design of large sprigs, and a dense design of trailing flowers, low neckline with v-shaped open front to bodice, and pleats at bodice back, sleeves extending to elbow, cuffs pleated at inside elbow and extending beyond sleeve width at back of elbow, full-length skirt pleated into the waistline with centre front opening, bodice and sleeves lined with linen: cotton fabric Indian, dress British, c. 1740 – 1760

It is a fine example of a dress that was made in England from cotton that was block-printed in India. Fabrics intended for export from India, and those designed in Europe, frequently combined florals with the more traditional Indian patterns to suit the Western aesthetic. Toward the close of the eighteenth century, the pattern might be printed on something other than a white background.

Here’s a close look at an 18th century textile that was block-printed and dyed using madder (Rubia tinctorum of the family Rubiaceae, the same family as coffee). It is homespun hemp and French. Madder is a herbaceous climbing plant and its roots have been used as a dye for over 5,000 years and can yield a variety of colors, though it is often associated with reds and pinks, and produces the well known “Turkey red” color.

Printed cottons reached the height of fashion for daywear in the 1780s. Their relatively crisp body, however, did not work as well with the classically-influenced gowns of the 1790s as they had with earlier styles, and diaphanous muslins began to take preference. By the first years of the nineteenth century, these loose, flowing prints were out of favor. Printed cottons lived on, however, as indispensible and useful materials from which to make gowns that didn’t show dirt on their busy patterns and could survive work and washing. And of course they hung on longer in outlying areas, where new fashions took longer to reach and dresses continued to be made from older fabrics because any fabric was valuable. Many people used lengths of fabric sitting around for years in chests, or remodeled older dresses into newer styles. In the 1810s and ’20s…the trend in fashion away from classical simplicity toward more constructed shapes and fussy trims resuscitated the popularity of printed cottons. – Jessamyn’s Regency Costume Companion

By the 1790s, mills in Europe with upwards of a thousand employees were adding to their availability by liberal copying of existing Indian patterns and through production of their own designs, like this 18th century block-printed cotton textile from France, below. The textile is part of the Collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

The amazing textiles from India influenced not only the development of fashion, but fueled the industrial revolution – stimulating the production in Britain of attractive, more affordable textiles on a large scale for customers in the expanding middle classes who wanted that India-influenced look. – Jenny Lister, V&A

The emergence of a middle class around the close of the 18th century coincided with the technological advances that made printed cottons more accessible. Soon cotton became an everyday favorite for many in England, France, Switzerland and Germany, throughout the Georgian era and beyond.

The majority of these women were in desperate circumstances due to unemployment, poor health, unsuitable living conditions and the like and would never be in a position to be raise their child. But many had hopes of being reunited – and the hospital asked for a small token as a means of identification, usually a piece of fabric, in case the mothers were ever able to care for the child again.

Assured that “great care will be taken for the preservation,” this distinctive bit of cloth (often cut by the mother into a memorable shape) was evidence was evidence of parentage.

Opened as a charity in 1739, London’s Foundling Hospital took in 16,282 anonymous babies between 1741 to 1760. Tragically, two-thirds of the foundlings died, and of the 16,282 babies taken in over the 19 year period above, only 152 were called for. The 5,000 swatches of fabric left by mothers now form Britain’s largest collection of everyday textiles from the eighteenth century.

Beautiful and poignant, each scrap of material reflects the life of an infant child and that of its absent parent. The enthralling stories the fabrics tell about textiles, fashion, women’s skills, infant clothing and maternal emotion…he importance of the Foundling textiles – 5,000 rare, beautiful, mundane and moving scraps of fabric – lies in the fact that so few pieces of eighteenth-century clothing have otherwise survived that can be identified with any confidence as having belonged to the poor. Ordinary people’s clothes were worn and re-worn by a succession of owners until they fell into rags, or they were cut up and reused for quilts, baby clothes, and the like. If, by chance, they outlived the eighteenth century, they were unlikely to excite the attention of collectors or museums.– Threads of Feeling

Fashionable garments of society women of the era have often found their homes in museums. Relatively few examples of the clothing of the common woman, worn and used to its limits, have survived.

The Foundling collection includes a whole range of textile fabrics worn by ordinary Georgian women – including the many samples of printed cottons and linens that comprise nearly one-third of the swatches, like these shown here. The custom of leaving tokens with babies lasted until the 1760s, when receipts were introduced. But by then the practice was so established that babies continued to be left with tokens so that by 1790 they numbered over 18,000.

The tokens deposited there demonstrate that even women at the very bottom of the pile – obliged to give up their babies because of poverty, illness and family breakdown – were able to participate in the new economy of pretty things. Their dress may not have been a new one, but they had managed to acquire something that pleased the eye and soothed the touch. They had, perhaps, been able to express a preference for spots over stripes or wondered whether blue was more flattering than green. The tokens left behind at the hospital show a remarkable variety of design. Indeed, reports Styles, it is rare for the same pattern to recur among the hundreds of different prints. Even poor women, it seems, were able to pick and choose. – The Guardian

Here is a close-up of the stunning print on the garment that helped shaped what we saw Demelza wear during Season 1 of the MASTERPIECE PBS series.

Set in 1780’s Cornwall, England, the Georgian era Poldark seems a good opportunity to showcase the Indian style block-printed cotton dresses of the era, but the designer has additional concerns: the costumes need to feel real with the right colors and tones, the fabrics have to hang well, and the “costumes have to suit the individual actors but they also have to work within the various sets and locations.” As inspiring as the original cape was to Agertoft, she told Willow and Thatch that in the end she used very little printed fabric, saying “It was not a choice as such, it was to do with what was was available at the time and how if fitted in with the look and feel of the project.” And fashion in provincial Cornwall was not the same as it was in London, and with its different strata of society, certain garments would not be appropriate, further limiting what make it on screen. Still, some printed cottons were used in the costumes in Season 1.

Despite the economic struggles of Poldark’s Truro, the town did have an upper-class which includes the characters Elizabeth, Verity and Ruth Teague. In their costumes, we see both solids and prints, and some embroidered fabrics as well. In the Season 1 scene pictured below, Elizabeth is wearing what appears to be an Indian print inspired printed cotton. As the scene was a flashback, it probably was meant to be in the 1770s.

Would our less well-off characters in Poldark have worn Indian block-printed cottons? At the start of season 1, the year is 1783 and Britain is in a crisis of falling wages and rising goods prices. Season one covered the first two of Winston Graham’s twelve historical novels on which the series is based, and about season 2 Aidan Turner told journalists that “We pick it up exactly where we left off from last year.” That brings us to the year 1790, when the third book Jeremy Poldark opens. (The first seven books are set in the 18th century, concluding in Christmas 1799.)

As we have seen in the printed cotton textiles from the Foundling Museum (above), even women living in poverty in the mid-1700s in London would have been wearing block prints. Truro is not London, but is likely that our characters of all classes could have regularly worn the Indian influenced printed cottons.

Tattered corset and red rouge in tow, Keren arrives in Cornwall with a group of traveling performers–and works her way into Mark Daniel’s heart with a similar pageantry. In her heartless quest for comfort and stability, Keren will stop at nothing to achieve her own selfish agenda. – PBS

In the photo above, it appears as if Keren might be wearing a skirt made from a hand painted fabric; it looks a lot like the painted late 18th century Indian fragment below. But Willow and Thatch thinks that seems far too fine for such an unfortunate character as Keren. The original below is cotton and its technique is black outline drawn on; mordants for 3 reds and 2 purples applied (sometimes over resist) by pen or brush; blue applied by brush over resist; yellow (over blue for green) applied by brush. My guess is that Keren’s skirt is block-printed, though perhaps it is a mix of printing and painting.

But we are talking about Keren, who said “And whose business is it, where my eye delight?” – so maybe she stole it!

According to Demode, “In the 1790s, small floral “sprig” designs with tiny motifs on pastel backgrounds became cheap, and therefore became popular for working class clothing.”

Although some countries passed legislation against the import, manufacture, and sale of painted and printed cottons in order to protect domestic textile industries (as in France from 1686 to 1759 and England from 1700 to 1774), by the 1730s printed cottons were serious contenders in the European clothing and furniture market, with their largest popularity from the 1780s onwards. While most printed cottons continued to be manufactured in India until the 1790s, mills in England, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland began to produce their own versions. – Kendra Van Cleave

In the photo below taken during filming of Season 2, Heida Reed (as Poldark’s character Elizabeth) can be seen wearing a dress made from a fabric with an Indian feel. So perhaps printed cottons of all styles, including sprig patterns, will be liberally worn in season 2 of Poldark.

Willow and Thatch can imagine one of leading ladies wearing something like this British printed cotton dress circa 1796, in Season 2.

In season three of Poldark circa 1795, Elizabeth’s cousin Morwenna Chynoweth (below) – played by actress Ellise Chappel, wears a fair amount of dresses that appear to be block printed.

Above: In the 1770s and 1780s printed cotton fabrics began to replace silk in popularity for women’s gowns. The material of this gown has a dotted ground and is printed in a repeating pattern of floral sprays. The lack of decoration and use of cotton instead of silk indicates that this gown was probably worn during summer afternoons for card games and tea parties, rather than for evening dress.

Above: The fabric for a circa 1790s gown is a hand-woven wool with silk and linen thread, block-printed in pink and green with a floral sprig central design, and a border suggesting chiné stripe. At the hem is a wider border edged with the same, and with a larger scale dentilated design. Cashmere shawls were prized imports from India during the late 18th century. British manufacturers soon began making shawls in similar styles. Not only were they worn with the newly fashionable Neo-classical gowns, the shawls were also made into gowns.

This German printing block, shows how the chiné stripe border was achieved.

Below: From a woman’s gown of white cotton (sewn circa 1780), block-printed (circa 1775) in a design of vertical undulating and branched yellow scaly stems through which are threaded branched floral trails in black with red and green, purple, with hand-painted blue hare-bell like flowers, and sprays of red leaves. The restrained decoration illustrates the growing influence in the Neo-classical style in textile design.

The bodice meets at centre front. The back is cut in a curve to point at the centre back. It is lined with linen and was probably boned at the centre back. There are traces of stitching from half way along the sides to the back where the skirt was attached. The back is made of 4 shaped pieces, tapering to a point at centre back below the waist. The bodice and sleeves are lined with bleached linen. Stitching either side of the centre back seam created casings for bones (missing), with small openings for them in the lining just below the neck line.

Cotton, either plain white or printed with brightly coloured patterns, had displaced silk as the most fashionable fabric for dresses at the end of the eighteenth century. Manufacturers in Europe emulated hand-painted cottons imported from India, and developed new technology which increased productivity and made printed cotton more affordable. English printed cotton dominated the markets of Europe and North America. Three blue threads woven in both selvedges were required by statute to distinguish English cottons from those of foreign manufacture, which were subject to a higher level of tax between 1774 and 1811. – V&A

We needed to identify a potential exhibition object – an early 1800s muslin dress – to display in the forthcoming The Fabric of India as an example of Bengali muslin use in Europe. Anyone who has watched a TV or film version of Pride and Prejudice will be able to picture the kind of thing we had in mind. Ideally suited for tall, slender women, the high-waisted ‘Empire Line’ style dominated fashion for at least three decades, from the 1790s to the 1820s. This fashion was totally dependent on a supply of fine, translucent cotton muslin – at first imported from India, then later, less exclusive imitations often woven and printed or embroidered in Britain. – Avalon Fotheringham, V&A

Textiles had been printed using a copper plate since the mid-18th century, but around the turn of the 19th century, England introduced a method of printing via a mechanical copper roller. That, and an increased supply of block-printed fabrics meant greater quantities of printed cottons were available at lower prices. Hand-painting and woodblock printing could add additional colors to the copperplate prints. As English women beyond the most affluent would have had access to Indian and Indian-inspired block print fabrics (even if it meant waiting for a relative from London to bring a bundle), it is no surprise that these printed cotton articles are being worn – and discussed – by characters in period dramas adapted from Austen’s classics.

Consider this interchange (flirtation!) about Indian textiles in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey between the “sprigged muslin robe with blue trimmings” clad Catherine Moreland, Henry Tilney and Mrs. Allen. (Volume 1, chapter 3).

They were interrupted by Mrs. Allen: “My dear Catherine,” said she, “do take this pin out of my sleeve; I am afraid it has torn a hole already; I shall be quite sorry if it has, for this is a favourite gown, though it cost but nine shillings a yard.”

“That is exactly what I should have guessed it, madam,” said Mr. Tilney, looking at the muslin.

“Do you understand muslins, sir?”

“Particularly well; I always buy my own cravats, and am allowed to be an excellent judge; and my sister has often trusted me in the choice of a gown. I bought one for her the other day, and it was pronounced to be a prodigious bargain by every lady who saw it. I gave but five shillings a yard for it, and a true Indian muslin.”

Mrs. Allen was quite struck by his genius. “Men commonly take so little notice of those things,” said she; “I can never get Mr. Allen to know one of my gowns from another. You must be a great comfort to your sister, sir.”

“I hope I am, madam.”

“And pray, sir, what do you think of Miss Morland’s gown?”

“It is very pretty, madam,” said he, gravely examining it; “but I do not think it will wash well; I am afraid it will fray.”

“How can you,” said Catherine, laughing, “be so—” She had almost said “strange.”

“I am quite of your opinion, sir,” replied Mrs. Allen; “and so I told Miss Morland when she bought it.”

“But then you know, madam, muslin always turns to some account or other; Miss Morland will get enough out of it for a handkerchief, or a cap, or a cloak. Muslin can never be said to be wasted. I have heard my sister say so forty times, when she has been extravagant in buying more than she wanted, or careless in cutting it to pieces.” – Northanger Abbey

Pictured below from a scene in the 2007 PBS MASTERPIECE period drama Northanger Abbey, Catherine is actually saying goodbye to James Morland and John Thorpe (and not Tilney) when they leave Bath, but throughout the film, she wears several printed cottons and Indian inspired dresses.

For anyone who wants to dig deeper into Austen’s inclusion of the discussion of the muslins in Northanger Abbey, you’ll be interested in the 2015 scholarly paper “True Indian Muslin” and the Politics of Consumption in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. Published in the Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies, Lauren Miskin “argues for a new understanding of the gender and imperial politics at work” in the novel.

In Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey (1817), Henry Tilney exhibits an unusual interest in women’s dress, claiming to “understand muslins” and announcing his predilection for muslins of the “true Indian” variety. This essay examines how Henry’s consumerist tastes are informed by his patriarchal privilege as well as Britain’s imperial practices. A self-proclaimed “excellent judge” of the market, Henry distinguishes genuine Indian textiles from their cheaper counterfeits and deploys this expertise to discriminate between honest women and pretentious coquettes. Henry’s regulatory tactics replicate the imperial strategies of British merchants who established policies of regulation and surveillance in order to exploit and eventually appropriate India’s manufacture of “true” muslin. By highlighting both Henry’s patriarchal privilege and muslin’s imperial history, this essay argues for a new understanding of the gender and imperial politics at work in Austen’s Northanger Abbey. – “True Indian Muslin” and the Politics of Consumption in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey

Designer Dinah Collin and her team had just over two months preparation time for the costumes of Pride and Prejudice, and wanted a fresh feeling for the girls’ summer dresses. Collin said she realized that they would most likely need to print the fabrics, as many of the Indian prints that were available had more modern, recognizable patterns that would need to be muted and altered with a color wash. Instead, she worked with a friend of her daughter who created and printed the Indian-esque fabrics that we see in the costume drama. According to the BBC, “Elizabeth’s clothes were designed to complement her practicality and active nature. Dinah deliberately chose earthy colours like browns, and ensured the clothes would allow Jennifer Ehle to move easily and naturally.”

We see quite a few lightweight cotton muslin dresses on the Bennet sisters in the 1995 adaptation, including these below, with their Indian block print styles.

Charlotte, played by Lucy Scott, is wearing a rather traditional looking all-over Indian block print pattern, similar to the designs below.

Can you think of other characters in Georgian and Regency era costume dramas who have worn the Indian block print style? I’ve recently seen them in two Victorian period dramas – the America Civil War era Mercy Street, and in Doctor Thorne, which is set in England in 1855.

The Oberkampf copper plate printed cotton above dates from about 1780, and was likely dyed using madder. According to the V&A, “This printed scene of idealised rural pursuits, musicians playing bagpipes and simple wind instruments, and a shepherdess-like girl collecting flowers in her apron, all in a rustic setting, is typical of the pastoral scenes printed on cotton textiles in the late 18th century.” It was intended for use in furnishings, rather than clothing.

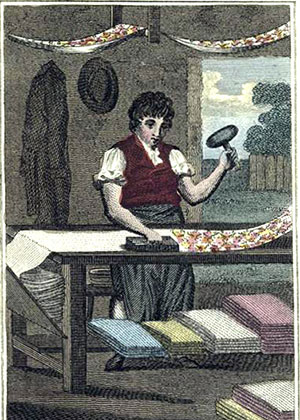

Above, a 1783 linen printed by Oberkampf Manufactory which shows various scenes depicted the method of textile printing at the Jouy-en-Josas factory:

This is one of the best known copperplate-printed textiles produced at the Oberkampf factory and it presents an abundance of information regarding the complexity of the textile printing process. There are a total of fourteen different scenes depicting activities involved in the process. The designer, Jean-Baptiste Huet, and a female colleague are depicted outdoors sketching, dyers mix colors, and printers apply the printing bocks. The drying of the finished cloth on the grounds of the factory completes the picture. The concept of printing scenes from a manufacturing process exemplifies the Enlightenment fascination with human accomplishments. – The Met

With the opening of the Eastern markets, Indian printed cottons found their way into France. At first they were very expensive, and French manufacturers tried to copy them by printing designs with wooden blocks on cotton. The silk and wool industries objected, and numerous edicts forbidding the importation or manufacture of printed textiles were issued. The edicts were universally ignored, and by 1759 all restrictions had been removed. Factories for the production of printed cottons opened in Nantes, Rouen, and Lyons, but the most famous center was at Jouy. Its founder, Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf, developed a system of fast-color dyeing and invented the copperplate printing process. – V&A

In the same year, Scotsman Thomas Bell made a significant advancement in copper plate printing when he invented roller printing. He realized that a continuous roll of fabric could be machine printed if a copper plate was curved around a roller. Unlike Oberkampf’s method, it had the advantage of being fully mechanized, and could do the work of 20 hand-block printers, but could only print a pattern that repeated for the full length of the fabric.

Willow and Thatch has read claims that Oberkampf invented the method, but the V&A holds that he only began using roller printing in 1797. According to that timeline, the Oberkampf 1799 dress below could have been printed using the copperplate roller printer, or by traditional copper plate hand printing. (Or perhaps through a combination of methods to achieve more than one color? As you’ll see below, in the early years of roller printing, there were issues printing more than one color.) The engraver Jean-Baptiste Huet, the principal designer for the Jouy factory between 1783 and 1811, probably designed the pattern on this toile de Jouy day dress, which has been identified as les bonnes herbes. (V&A)

Below is an example of a one color fabric that is solely roller printed, circa 1830s, around the time that the use of the machines was in full swing. Though textile historians differ on when it became possible to print multiple colors with the new machine, we know that registration issues initially limited the process so that just one color could be achieved. The roller printer was in general use by the first decade of 1800s, and within 100 years of its invention, the process allowed eight colors to be printed on both sides of the fabric. (Clues in Calico – A Guide to Identifying and Dating Antique Quilts)

But the roller printer didn’t immediately, or entirely, replace the hand block-printing method:

The early machines could print only one color but designs were often enhanced with additional colors added by block printing. By 1860, roller printing machines could print up to eight colors simultaneously and toward the end of the nineteenth century textiles with more than twenty colors were produced. Wood-block printing was the earliest form of textile printing and continued well into the nineteenth century, despite the fact that copper roller printing was faster. This was due to the fact that the rollers were limited as to the size of pattern they could produce, therefore high-quality hand-block and copperplate prints still had the advantage of being able to provide a large-scale design of the type preferable for household furnishing textiles. Block printing was not completely replaced by the roller until the second half of the century. – The Met

In the Kent State Museum Collection is a nice example of a late Georgian (circa 1825 – 1829) English printed cotton day dress: White striped cotton printed with green, pink and red sprays, day dress. Dress with gathered shoulders and wide neck with gathers pulled to center of high waist, dropped armseye, ruffle cap over ’gigot’ sleeve.

It isn’t specified if the fabric is entirely block-printed by hand (by then it is likely that a multi-color English made cotton was both roller and block-printed), but you can see how the Indianesque style was still relevant in England in the late 1820s.

Below are some plates that show patterns for muslins in the late Regency period and toward the close of the Georgian era. Though the origin of the plates is not cited, they are presumably American or English.

The fabric, which must first undergo special preparation, is laid on a low bench on a pad formed of several thicknesses of cloth. The printer squats in front of this, with the dye in a pan or earthen vessel at his side. In this vessel is a frame which is covered with one or more thicknesses of heavy cloth or blanket forming a pad which becomes saturated with the color, and on which the blocks are pressed before stamping. Besides being used for applying the dye, blocks may be used for the mordant, and, in some places, especially southern India, wax or some resist is often stamped on the cloth. – Block Prints from India for Textiles

This textile below is a Williamsburg 18th century reproduction, in cotton. Sisters Rebecca & Ashley of A Fashionable Frolick say that “It features a block-printed or stamped design with flower motifs that you see quite frequently in 18th-century textiles from the 1750s through the 1780s. The ground is a natural, unbleached color with a linen look, making this ideal for lower or working-class reproduction clothing. This would make an absolutely gorgeous gown and matching petticoat, or a very pretty little jacket or bedgown to pair with a solid colored petticoat.”

They also have available a linen – cotton fabric that is an exact reproduction of an original block-printed fabric in the collection of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum. They suggest that it would make a fabulous reproduction fitted jacket or bedgown.

You can visit Fashionable Frolick’s store here: 18th-century reenactors, sisters Rebecca and Ashley have been researching and recreating historical fashions and accessories for over ten years. Here you will find only the finest quality materials, fully researched and documented styles and designs, and construction techniques copied directly from period sources. Every stitch is hand sewn and we never use any modern shortcuts to ensure that you will always receive the most accurate reproduction item possible. Our creations are well suited to museum settings, reenactors, and the discerning historical costume enthusiast.

Wm. Booth, Draper carries several cottons that reproduce the print and drape of late 18th century fabrics. Suitable for re-enactors wanting to sew historically accurate outfits, the fabrics are accurate copies taken from 18th-century garments in museums around the world. They’ve recently adding a lot of very fine cotton plain, sprigged & flowered muslins, that may be perfect for your Regency gown.

Reproduction Fabrics sells cotton fabrics for specific time periods between 1775-1950. Renaissance Fabrics is another good supply of cottons for the historical costumer.

The Colonial Fabrics line from Williamsburg Marketplace currently carries 12 cottons that are reproductions of antique fabrics kept in the Colonial Williamsburg collections. Two are block-printed.

Duran Textiles in Sweden offers some hand block-printed and painted cottons (and silks) that are reproduced from 18th century original patterns.

About the collection: Several 18th century cotton printers are known from Sweden, mainly thanks to the research and the publications of the Swedish textile historian Ingegerd Henschen. In India it was possible to reproduce the old patterns. Production is small scaled, and in some aspects it is still using 18th century technology, which gives our fabrics an authentic character. All fabrics are hand printed. Like the silks, we made all the patterns in at least two different colours to make the collection balanced and commercial. We chose a quite heavy 100% cotton fabric as ground for the prints. It resembles the hand woven original fabrics, made from hand spun yarns. This quality is fitting both for clothing and furnishing, in the same manner as the 18th century cotton prints were used.

This fragment below from the Victoria and Albert Museum collection was made in the 18th century in India, and is printed, painted and dyed cotton. It is a traditional repeating pattern of staggered rows of yellow roses. It may have been made in Burhanpur in the northern Deccan, a known center of production of printed and painted textiles. Cotton fabrics with repeating floral designs like this one were usually used for garments at the royal Mughal and Deccani courts.

If you are looking for a cotton fabric with a similar pattern to sew your own period dress, this or this might do. If you are feeling crafty, you could also try your hand at printing your own version using this vintage hand carved printing block with a Mughal / buti flower pattern, or another from the many beautiful blocks that are sold by Heritage Collectible.

The original that inspired Lily’s dress is a circa 1800s English round gown (below). Augusta Auctions, North America’s premier auction house for historic costume, couture & vintage fashion and rare textiles, describes the gown (below) as follows: White ground printed w/ small scattered red, pink, purple & blue leaves & flowers, gathered 4 band drop front bodice w/ shoulder buttons, center back ties, short tucked sleeves trimmed w/ lace, pair blue threads in selvedge, linen bodice & sleeve linings.

The fabric on the original round gown is remarkably similar to this 18th century textile from France. Part of the collection at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, it is relief printed on a plain weave cotton.

You might also want a how-to book to guide you through the technique. For ideas, you could try John Robshaw Prints: Textiles, Block Printing, Global Inspiration, and Interiors.

If you want to do more research on traditional Indian block-printed fabric, this book by Ruth Barnes might be a good resource. A detailed scholarly catalogue of the collections housed in the Kelsey Museum, the book includes Indian block-printed cotton textiles from the 13th century onwards.

Also of interest is Wearable Prints, 1760-1860: History, Materials, and Mechanics in which author Susan Greene surveys the history of wearable printed fabrics, which reaches back into the earliest days of the discovery of the delights of selectively patterned cloth and is firmly interwoven with the Industrial Revolution. The bulk of the book is devoted to the process of printing and dyeing. Greene brings together evidence from period publications and manuscripts, extant period garments and quilts, and scholarship on 18th and 19th century chemistry and technology.

And be sure to see A Lady of Fashion: Barbara Johnson’s Album of Styles and Fabrics: A British reverend’s daughter named Barbara Johnson (1738-1825) kept a meticulous diary throughout most of her life (1746-1823) of the fabrics she used (including printed cottons) and details of the garments she made with them. The book also discusses the social background of the period. The original diary is now a part of the Victoria & Albert Museum’s collection.

Johnson’s album consists of ninety-seven pages of paper with textile samples and fashion plates attached, along with her descriptive notes.

At the end of this post you’ll find links to more articles and books about block-printed textiles in India and Europe.

The DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum will exhibit Printed Fashions: Textiles for Clothing and Home. Opening March 25, 2017 in the Gilliland Gallery in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, this should be particularly enriching for anyone interested in America in the 18th century.

Colonial Williamsburg has not previously showcased its superlative collection of printed textiles that range in date from the late 17th century into the 19th century. With their stunning designs and bright colors, the objects in this exhibit will be a feast for the eyes. Printed fabrics were used to make fashionable clothing and to upholster home furnishings. While visually arresting, printed textiles also had economic importance as trade goods and as examples of technological advances. A variety of techniques were used to create innumerable patterns. Fabrics were resist printed, block-printed, copperplate printed and roller printed. Each of these required different manufacturing skills and resulted in a wide range of designs and patterns available to the 18th-century consumer. On view will be over 75 objects including gowns, quilts, men’s waistcoats, curtains and bed furnishings. More information about the exhibit can be found here.

Also in the U.S. is The Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, which has a stunning collection of textile samples, like those in the Dyer’s Record Books. The 19 books span from 1812 to 1886, with over 2,000 digitized pages of block and roller printed textiles from both England and America. The Textiles department represents the full spectrum of woven and non-woven techniques and a wide variety of printing and dyeing methods.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art also has some nice block-printed fabrics in its collection, like this late 18th century cotton from France.

And of course there is also The Metropolitan Museum of Art, with its Antonio Ratti Textile Center:

Objects from the Museum’s 36,000 textile pieces (excluding the holdings of The Costume Institute) are featured throughout the Museum, in galleries overseen by each of the 10 curatorial departments that collect textiles. In addition, selected textiles from the collection are featured, on a rotating basis, in a small gallery at the entrance to the Antonio Ratti Textile Center; others can be examined in the center’s study rooms with advance appointments.

About 1,000 textiles—samplers and other needlework; quilts and coverlets; 19th- and early 20th-century printed textiles; handmade rugs; and fabric commemoratives printed or woven in honor of historic occasions—are housed within the collection of The American Wing. The department also has a significant collection of work by Candace Wheeler (1827–1923), America’s first important female textile designer. The Wheeler collection encompasses printed, woven, and embroidered pieces.

European textiles from the Renaissance through the early 20th century are overseen by the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts. Among its approximately 17,000 pieces are woven, embroidered, painted, and printed textiles.

The Department of Islamic Art contains approximately 2,000 textiles, from early inscribed (tiraz) and printed examples to dye-patterned cottons, brocades, velvets, and embroideries from the 16th- and 17th-century courts of Safavid Persia, Ottoman Turkey, and Mughal India.

The center’s reference library contains approximately 3,400 books and journals devoted to the historical, technical, and cultural study of textiles. Computer terminals provide access to the collection database, which offers images and descriptive information about the Museum’s textiles, maximizing the information available to scholars and the public while minimizing the textiles’ exposure to light, dust, and handling. The library is open to the public without an appointment, but use of the computers should be scheduled in advance. All of the library’s holdings appear in WATSONLINE, the Museum libraries’ online catalog, and most are also accessible to outside researchers through the Thomas J. Watson Library.

In England, the Victoria and Albert Museum houses a strong collection of block-printed textiles. The national collection of textiles and fashion, which includes more than 75,000 individual objects or sets of objects, span a period of more than 5,000 years, from Predynastic Egypt to the present day. Almost all textile techniques are represented in the collections, including woven, printed and embroidered textiles, lace, and tapestries. Be sure to check out the page for their 2015 exhibit The Fabric of India which “looks at both the technical aspects of textile production and its artistic value.”

The National Trust Collections is also an excellent resource of printed costumes and textiles. The National Trust cares for one of the world’s largest and most significant holdings of art and heritage. No other organisation conserves such a range of buildings, collections, gardens and settings intact, nor provides such extensive public access. I just love this circa 1820 poke bonnet made from straw plait; it is fully lined with glazed cotton that is roller printed and block printed with floral stripe design in several colors.

You may also want to know about Indian Block-Printed Textiles in Egypt: The Newberry Collection in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

If ever you are in France, you may want to visit the East India Company’s Museum, which has a textile department as part of its collections.

And don’t miss The Museum of Printed Textiles, in Mulhouse, France, who has a collection of Indiennes and also has some good information online.

The Musée de la Toile de Jouy (Jouy Printed Fabric Museum) commemorates the Manufacture des Toiles de Jouy, founded in 1760 by entrepreneur and printer Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf. At the museum, you can see collections of Toile de Jouy (“Indieenes” and fabrics with figure scenes), printing equipment, and old drawings. The manufacturer’s family, his lifestyle, and his keepsakes have not been overlooked: The eighteenth-century furniture, objects of value, and wardrobe evoke the world of Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf.

The permanent collection stretches across two levels, where you will have time to admire the many Jouy textile creations of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Costumes, samples, borders, preliminary prints (tests carried out on paper before printing), sections of fabric, curtains, and bed coverings will give you an idea of the multitude of motifs printed at Jouy, but also of their various uses, both for clothing and for interior decorating. You can also admire the general collections of French and foreign printed fabrics that were in vogue in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

In India, make a trip to Jaipur to the Anokhi Museum of Hand Printing. The museum focuses on contemporary fabric ranging from innovative designs created by talented artisans, to traditional outfits still worn in select regions today, albeit in dwindling numbers. A focused selection of historic textiles provides a context for further understanding of block printing.

To illustrate the breadth of the craft, textiles in the permanent collection display a range of natural and chemical processes including dabu mud-resist printing, and gold and silver embellishment. A display of wooden and brass blocks with carving tools highlights an aspect of the craft that is often neglected when discussing the beauty of printed cloth. Here’s a look inside the museum.

The Textile Society, for the study of the history, art and design of textiles, has a list of recommended museums.

In my possession is a copy of Decorated Paper Designs 1800, a book filled with a vast selection of designs, many of which were block-printed and were inspired by textile patterns. Here are some of my favorites, drawn from the collections of book restorer Jacques Koops and antiquarian book dealer Johannes Marcus.

Block-printing is a technique that was first introduced for the decoration of textiles, later becoming one of the most popular methods for decorating paper. Although there are various forms of block-printing using different materials, the techniques are very similar. The most frequently seen block-printed papers are usually referred to as chintz paper. Chintz was originally a dyed and printed cotton fabric from the Coromandel Coast, the renowned textile region in east India. For centuries, decorated textiles from this region were were sought-after items in the trade between south and southeast Asia, China, japan and Arabia. Later, in Europe, these oriental textiles were traded in the ports of Naples and venice or arrived overland via Turkey.

Original Indian chintzes were typically decorated with floral and foliate patterns, embellished with complicated details and elaborate border designs. Chintzes were made with wooden blocks and brushes, and the textiles were usually glazed by polishing them with shells. From the seventeenth century, European colonial powers, especially England and Holland, were very active in the textile trade in Asia. Initially, the objective was to sell Indian-made textiles further east, but gradually a textile industry emerged in Europe to serve both the European and Asian markets. Decorated textiles could be made more cheaply in Europe using efficient, mass-producution facilities. Some workshops actually produced printed cottons and papers simultaneously. – Decorated Paper Designs 1800

I consider myself very fortunate to own a little block-printed quilt like this one. Made of voile cotton, it is the best, lightweight cover a gal could ask for on a warm summer’s night when you still want a little something over you. And so pretty.

Because beautiful, traditional, high-quality block-printed textiles are still readily available, it’s an easy collection to commit to. While both vintage and contemporary originals can be pricey, the preponderance of choices of styles and objects means that the dedicated collector will be certain to find something in budget.

This organic cotton, indigo and madder dyed Royal Lotus print block-printed fabric is just $14.00 a yard.

Willow and Thatch quite likes this whimsical pattern, maybe it is a fern? It is being sold as five yards for about $30.00.

And here is a very affordable pattern along the lines of “undulating trails of exotic flowers,” hand blocked on cotton.

I hope this post gives you a better understanding of the history of the block-printed cotton in Europe, and why our favorite characters from Georgian and Regency era costume dramas would be wearing them. I also hope this helps you to source reproduction printed cottons for your historical sewing projects, find a new collecting passion, or try your hand at the craft. Enjoy!

Links to further reading on block-printing in the 18th century, and related topics:

A Lady of Fashion: Barbara Johnson’s Album of Styles and Fabrics

America’s Printed & Painted Fabrics 1600-1900: All the Ways There are to Print Upon Textiles

Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West

Consuming Modes in Northanger Abbey: Jane Austen’s Economic View of Literary Nationalism

Empire of Cotton: A Global History

English Chintz, Victoria and Albert Museum

English Printed Textiles, 1720-1836, Victoria and Albert Museum

European Textile Printers in the Eighteenth Century: A Study of Peel and Oberkampf

Fabric a la Romantic Regency: A Glossary of Fabrics from Original Sources from 1795 – 1836

Fashion in the Time of Jane Austen

French Textiles: From the Middle Ages through the Second Empire

Go Gothic with Northanger Abbey: Guest Blogger Kali Pappas Chats about Movie Fashions

Indian Painted and Printed Fabrics

Just How Fashionable are Poldark’s Ladies? – Frock Flicks

Nineteenth-Century European Textile Production

Perfect Partners: Muslin and Cashmere, V&A blog

Printed Textiles: British and American Cottons and Linens 1700-1850

Regency Fashion: Printed Cotton Fabrics

Regency Women’s Dress: Techniques and Patterns 1800-1830

Textile Production in Europe: Printed, 1600–1800.

Textiles in America, 1650-1870

The Dress of the People: Everyday Fashion in Eighteenth-Century England

The Fabrics of Mulhouse and Alsace 1750-1800

The Red Dyes: Cochineal, Madder, and Murex Purple: A World Tour of Textile Techniques

“True Indian Muslin” and the Politics of Consumption in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey

Toiles de Jouy: French Printed Cottons, 1760-1843

September-October 2010 issue of the textile magazine Selvedge, features an in-depth cover story on the Threads of Feeling exhibition.

Wearable Prints, 1760-1860: History, Materials, and Mechanics 18th Century Printed Cotton Fabrics

Whatever Shall I Wear? A Guide to Assembling a Woman’s Basic 18th C. Wardrobe

32 Step Visual Presentation of the Block Printing Process

Need more? Willow and Thatch has a board on Pinterest dedicated to Block Printing. Jane Austen’s World has terrific Regency era Pinterest pages and this board is also great for printed fabrics of the era. And remember to visit the Period Films List; you’ll especially like the Best Period Dramas: Georgian and Regency Eras List.

A lot of research went into this post with the aim of historical accuracy, but by no means is Willow and Thatch an expert on any of the above; if something isn’t accurate, please do let me know so it can be made right.

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave