While we may all agree that there’s no such thing as watching “Pride and Prejudice” too many times, there’s always room to read a new, good book. If that book includes an original take on Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy, and brings deeper insight to other characters, all the better.

To help keep this site running: Willow and Thatch may receive a commission when you click on any of the links on our site and make a purchase after doing so.

Below, Janeite Abigail Kunkel dives into Jan Hahn’s novel An Arranged Marriage: A Pride and Prejudice Alternate Path (2011), and shares why both those interested in Jane Austen’s life, and fans wanting more of her 1813 classic, will want to read it.

Jan Hahn’s novel An Arranged Marriage: A Pride and Prejudice Alternate Path imagines an alternate ending to Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice: Elizabeth accepts Mr. Darcy’s second proposal not as a result of the revelation of the actuality of his genuine care for her and general benevolence, but because it is necessitated by her family’s financial crisis following the death of Mr. Bennet.

Hahn’s central intent is intimated by Elizabeth’s own pointed reflection on the elucidating letter she received from Darcy following her initial refusal to marry him, that “much was gained by reading between the lines.”

Where Elizabeth looks to this letter to “[e]nlighten [her] to Mr. Darcy’s character,” Hahn reads between the lines of Pride and Prejudice not simply to develop preexisting facets of the plot and characterizations, but as a means to elaborate on characters who are not at the forefront of the original work and to engage with Austen’s own biography.

Through this exploration, Hahn ultimately raises compelling questions about standards of feminine success that are inextricable from Austen’s literature and life.

Hahn makes significant plot changes throughout the book: the death of Mr. Bennet which catalyzes Elizabeth’s arranged marriage to Mr. Darcy; the sequence of Jane and Mr. Bingley’s eventual engagement; and the invented sub-plot of a servant called Fiona who is mother to a young son, and who Elizabeth initially fears was impregnated by Mr. Darcy. But she later discovers that, in fact, it was merely Mr. Wickham who was responsible for yet another woman’s disgrace.

In addition to these imagined sub-plots, Hahn concludes the book by depicting endings for minor characters left undisclosed in Pride and Prejudice or elaborating on elements of the novel’s ending.

Much of the “reading between the lines” in the text is a result of Hahn’s active dialogue with the conclusion to Austen’s novel. Although perhaps most audience members would have assumed as much regardless, Hahn characterizes Lydia and Mr. Wickham’s marriage as one riddled with both financial difficulties and infidelity. She also briefly details how Kitty married “the local curate, Mr. James Morris” in Longbourn.

Crucially, although in the original novel Mary is perhaps the most forgettable sister, Hahn allocates more time to detailing her outcome than Lydia and Kitty’s combined.

In fact, Mary’s end bears some resemblance to Austen’s biography. By developing Mary’s story and writing certain elements of Austen’s own life onto the character, Hahn seems to suggest that Mary may have been, at least to a degree, a reflection of Austen herself.

Hahn’s “Mary” never married, wrote “witty, satiric romances” to delight her family before a male relative (Mr. Gardiner) facilitated their publication in London to great success, to the point where “the books became so popular she eventually took a house in London where she enjoyed the company of many cultured and erudite persons of the arts.”

This bears a certain resemblance to Austen’s own biography. Along with the fact that Austen became an author and never married, she was intently focused on the development of her knowledge from a young age, which is certainly Mary’s aim.

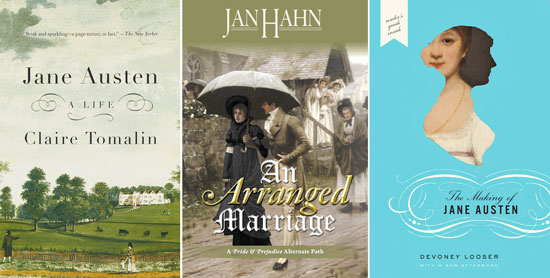

Austen’s brother Henry spoke of her remarking that it was hard to distinguish “‘at what age she was not intimately acquainted with the merits and defects of the best essays and novels in the English language,’” (Jane Austen: A Life, Austen, qtd. in Tomalin, 69).

Austen did also regularly share her writings with her family long before they were published (and many earlier writings went unpublished) which Mary is seen to do as she “sent her stories to [their] aunt in town for her enjoyment.” And, of course, Austen’s literature has experienced broad success and been acknowledged by “cultured and erudite persons of the arts.”

This proposition is also interesting to consider as not only was Austen known for her satirical portrayals of family in her novel’s characters — and often of her own family members as Hahn’s Mary does with “thinly veiled characterizations” — but Pride and Prejudice itself was written by Austen during a dark year of her life where Tom Fowle, her sister Cassandra’s fiancé, died and Austen’s own romance with a Tom Lefroy came to a halt (Tomalin, 161).

In particular, her unsuccessful courtship with Lefroy may have contributed to a grim characterization of herself in Mary who — perhaps consistent with Austen herself — chose to focus on developing accomplishments over romance.

Hahn also gives voice (through the narration of Elizabeth) to concerns that Mary (or any unmarried female author) would write “a spinterish version of Fordyce’s Sermons aimed at warning young women of the perils of attending too many balls, unchecked flirting, and the dangers of the opposite sex,” but instead discovers her to have written clever romances including composite characters of her family members just as Austen did.

As such, even while Hahn hints at the difficulty in Austen’s own personal life as the inspiration for Mary, she also highlights the compelling nature of her work — which, along with her Mary, did not consist of a catalog of “spinsterly” novels by any means.

That said, there are some distinctions between this Mary and Austen herself. Contrary to Hahn’s depiction of Mary’s life beyond the original boundaries of Pride and Prejudice, Austen’s literary reputation was created posthumously.

As Devoney Looser explains in The Making of Jane Austen, her literary reputation was created “first by [family as well as popular reception and then] Austen’s legendary status was also driven forward in part by being mentioned, discussed, beloved, and detested by luminaries of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries” (4). Though it is nearly entirely uncontested that Austen occupies the same “space” as “cultured and erudite persons” in perpetuity — and materially on many bookshelves — she published anonymously and lived quietly during her own life.

Mary herself is not an example of an excellent reader in Pride and Prejudice but arguably an embodied humorous criticism of dull, moralistic approaches to literature whose life at the end of Pride and Prejudice is described as consisting of her remaining at home where she “was obliged to mix more with the world, but she could still moralize over every morning visit; and as she was no longer mortified by comparisons between her sisters’ beauty and her own, it was suspected by her father that she submitted to the change without much reluctance” (Austen, 365).

By contrast, in Hahn’s narrative, Mary is implicitly an excellent reader as she becomes a successful writer to the point that she gains both acclaim and a house in London. Still, if Mary is to be read as inflected by Austen’s own biography, perhaps Hahn’s character was inspired by the question of what may have happened if Austen herself had experienced fame during her lifetime.

Although Mary cannot be read fully as representative of Austen’s own character, Hahn effectively explores parallels between the character and Austen’s biography to elicit meaningful discussion about both her life and the broader gendered norms of success which would have likely weighed on her mind.

Hahn’s suggestion of Mary’s success following her sisters’ marriages is based on a sympathetic elaboration of Austen’s description of Mary’s life at the end of the novel. Hahn writes through the voice of Elizabeth, “I wish I could say that Mary made a like marriage [to Kitty’s], but it was not to be,” and expresses sympathy for Mary’s characteristic isolation. However, in depicting her success, Hahn does not frame Mary’s literary rather than marital life as conciliatory.

Similar to the end of Pride and Prejudice, Hahn’s Mary also welcomes the transition after her sisters each depart for their husband’s homes and, although she does still “moralize,” is exposed to and fluent in society afterwards — perhaps like Austen.

Given the continuities between Austen’s biography and Mary’s ending in An Arranged Marriage, it is telling that Mary flourishes only after escaping comparison to her sisters, who represent more ideal models of femininity in the period.

Hahn appears to be utilizing this exploration of Mary not only to develop a more favorable story for her, but also to raise questions about the pressures Austen would have experienced as an unmarried female author, namely, the emotional ramifications endured by women acting outside of the norm in a society where marriage was the determinant of success in a woman’s life.

As such, Hahn’s fairly explicit project of “reading between the lines,” does more than simply facilitate this new attention to Mary and other characters. It encourages readers themselves to collaborate in Hahn’s project and meaningfully engage with the gendered societal context of Austen’s works and the author herself.

An Arranged Marriage: A Pride & Prejudice Alternate Path (2011) is available HERE

Abigail Kunkel is an English Literature graduate from Pacific Lutheran University with minors in History and Holocaust and Genocide Studies whose interests are also firmly rooted in the long nineteenth century- especially Austen. She is compelled by the intersections of gender, trauma, and race endemic to these areas of research, and hopes to study them further in graduate school. It is hard for her to pinpoint exactly when she had her first engagement with Austen as she had read all of Austen’s books while growing up and devoured the film adaptations in quick succession; it is difficult to remember a time before having an awareness of her work and the community around it. Her initial enjoyment of the romantic and humorous elements of Austen’s work was later joined by an appreciation for the depth and sophistication of Austen’s often subversive moves, particularly in terms of gender. She is also an avid period drama fan and a jealous guard of her collection of Jane Austen’s DVDs (especially BBC’s Pride and Prejudice).

This article originally appeared in The Jane Austen Review, a nascent public humanities project that emerged from student-faculty collaboration at Pacific Lutheran University (Tacoma, WA). It is coordinated by Abigail Kunkel, Adela Ramos, and Madeline Scully with the goal of creating a digital home for non-academic and academic readers and writers interested in engaging with Jane Austen and her afterlives.

The Jane Austen Review publishes thoughtful review essays about Jane Austen retellings (fan fiction, fiction, web series, TV series, film), material culture (crafts, fashion, merchandise), or other manifestations of Austen afterlives, such as literary tourism. Their only requirements are that review essays make connections between Austen’s time and our own and that they are accessible to the general public.

They approach the editorial process with a workshop spirit, offering several rounds of feedback and guiding writers through the revision process because what excites them most is to share ideas and engage in conversation. You can pitch an idea by sending a DM via the Twitter handle @janeatplu or by sending an email to thephaetonreview at gmail dot com.

If you enjoyed this post, wander over to The Period Films List. You’ll especially like the Best Period Dramas: Georgian and Regency Eras list. Also see Old Maids & Mind Games in Austenland and the Movie Lover’s Guide: Sense and Sensibility.