Last Updated on April 14, 2021

In 1989, producer Kevin Sullivan had just finished making what would become two of his most enduring films, “Anne of Green Gables” and “Anne of Avonlea,” and he wasn’t sure what to work on next. He’d produced the second “Anne” film with Disney, which was looking for partners to create new material.

To help keep this site running: Willow and Thatch may receive a commission when you click on any of the links on our site and make a purchase after doing so.

“And someone said to me, Oh, no one’s ever really made a long-form series out of [Lucy Maud Montgomery’s] material. You’d be nuts not to do it,” Sullivan recalls. But rather than create a series following one character, he decided to set an ensemble “spinoff around the world of Avonlea,” where Anne lived.

The result was Road to Avonlea, the award-winning family series that ran for seven seasons.

To mark the thirtieth anniversary of the show’s premiere, we spoke with Sullivan about developing “Avonlea,” his memories from the sets, and why viewers keep returning to his cinematic worlds.

Sullivan’s wife introduced him to Avonlea

Even though L. M. Montgomery’s books are considered Canadian classics, Sullivan had never read them when his wife, Trudy Grant, encouraged him to adapt Anne of Green Gables into a film. At first he was skeptical. “When I first sat down and read that book, I thought, This is a book for 12-year-old girls. What am I doing with this?”

But the more he read of Anne and Montgomery’s background, the more he found himself drawn into the world of Avonlea. Despite a lonely childhood and personal tragedies, Montgomery found a way to escape into her imagination.

“She had all this turmoil going on in the background, and yet somehow she shone a light on the human condition,” says Sullivan.

He began to see a way to balance the beauty of Montgomery’s world with the darker aspects of life in the early twentieth century, while avoiding “the temptation to make it too sentimental or too saccharine.” Together with industry veteran Joe Wiesenfeld, Sullivan adapted the novel into a screenplay, beginning his journey into Avonlea.

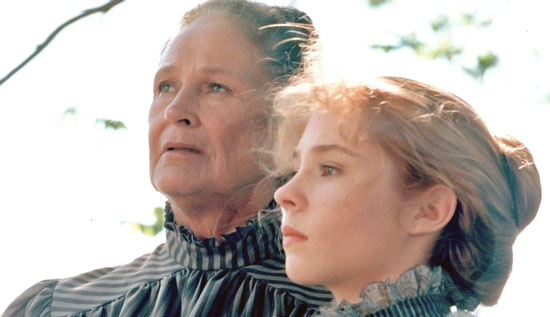

Actress Colleen Dewhurst helped him find the heart of Avonlea

On a recommendation from Katharine Hepburn, Sullivan approached veteran actress Colleen Dewhurst for the role of Marilla Cuthbert, Anne’s adoptive mother.

Unusually, “her agent called back about 15 minutes after I made contact,” Sullivan recalls. “He said, ‘She never does this and I have advised her against this, but she insists that she wants to be in this production.’”

As it turned out, “Colleen had a home on Prince Edward Island. She knew the mythology of Anne of Green Gables inside out, and she had this great, almost mystical sense of what Montgomery was, who she was as a writer, and who Marilla was.”

She readily shared her deep understanding of the story with Sullivan, coaching him on scenes and characters and helping him balance humor with heart. “She probably had the greatest influence on the sensibility of those two films,” he says.

But it wasn’t until the end of filming that Sullivan truly found the film’s soul, and again, it was all thanks to Dewhurst.

“Near the end of filming, she took me aside and said, ‘You’re missing something.’ I wasn’t even open to it at that point because the production was almost finished, [and] we were running out of time, schedule, money, everything, and she said, ‘No, really, listen to me.’ She read me five lines in the book, a tiny little footnote of what happens after Matthew dies and Marilla hears Anne crying in her room. And she [said], ‘This needs to be a scene. This is not in here. You’ve got to do this.’ So I sat down and wrote a scene just before we were to go on lunch, handed it to the two actresses, and it was one of the most remarkable performances I’ve ever seen. Marilla gets up in the middle of the night and approaches Anne and says to her, ‘You’re like my own flesh and blood now.’ It was staggering to see what happened. I did three takes, I used the first take, and to see the effect on the crew… that was a huge turning point, because I realized the power of the material. This wasn’t a story for 12-year-old girls; this was a story about the human condition.”

In that scene, Sullivan discovered the soul of Montgomery’s work: human connection. Her characters forge warm, lasting relationships in the face of great hardship, and Sullivan held onto that discovery as he finished the two “Anne” films and developed “Road to Avonlea.”

Road to Avonlea allowed Sullivan to flex his creativity

Unlike the “Anne” films, “Road to Avonlea” is a looser interpretation of Montgomery’s work. Inspired by the stories in four related novels, which follow other residents of Avonlea, Sullivan decided to borrow this “wonderful ensemble of characters” and develop original story-lines for them.

“[The material] wasn’t heavy on story; it was simply characters, and it was a dialogue and a sense of place. In fact, Montgomery’s whole ethos is ‘spirit of place,’ and [the idea] that Prince Edward Island has its own kind of aura. I wanted to inject my own sense of storytelling into Montgomery’s world, to not disrupt the world but to kind of find synchronicity in it.”

It’s this conversation between source material and Sullivan’s interpretation that define “Road to Avonlea.” He began each season with a blank slate, trusting in the process of pitching ideas with story editors and writers to mold the season’s arc. The show could evolve as needed.

“It was probably a lot younger and more family-oriented in the beginning when the characters were younger, but as they grew up the stories changed a lot. We started to explore more profound themes and that meant cultivating a different type of storytelling. It’s like curating an exhibit. You try to nurture the best elements of it, but you can’t always tell where it’s going to go, and so you have to be open to that process of failure and give and take and experiment.”

Little of the Avonlea productions were actually filmed on PEI

One of the most memorable aspects of Sullivan’s productions is the scenery: sea grasses waving in the breeze, sandy beaches tumbling down to ocean sunsets, and rolling fields lined with firs. Viewers are transported immediately to the rugged beauty of Prince Edward Island. Or are they?

It’s actually an impressive example of cinematic magic, since Sullivan filmed very little on PEI. This decision did not go over well with Canadians at first. “When I made the ‘Anne’ films people were very upset that I wasn’t going to film the whole thing on Prince Edward Island, because [Anne] is a Canadian classic,” Sullivan says.

“[But] when you’re creating worlds in cinema they are always made up, and it’s how good you are at [that] process that convinces the audience whether the world is seamless or not. So I decided, let’s film what we need to on Prince Edward Island to give it that look, but we’re not going to go there and move units at excess amounts of money that I didn’t have the budget for; I’m going to try and uncover that world in Ontario.”

Sullivan and his team scoured Ontario for the perfect locations. Two buildings in Uxbridge, north of Toronto, served as the exteriors of Green Gables, and one of them was built next to a field lined with fir trees.

“It looked like it just came from Prince Edward Island,” Sullivan says. So when he began production on “Road to Avonlea,” he returned to Uxbridge. “Why am I going to go running around looking anywhere else?” he said to himself. “This is it. Let’s just build a whole town here.”

So the exteriors of Avonlea sprouted around Green Gables, while Sullivan shot interiors at a studio in Toronto. “It was like being on location, but our standing sets in-studio allowed us to film episodes within a ten-day production schedule.”

Actress Megan Follows set the standard for young actors

Sullivan has a knack for drawing natural performances out of his young actors, and he owes it partly to Megan Follows, who played Anne Shirley. “She was a chameleon,” he says. “What you see onscreen is not Megan Follows. She created that character [and] found all the elements [of her character] to project them very cohesively.”

Follows, who hailed from a family of actors, also understood how to perform in front of a camera, and the other children were able to learn from her experience.

“So often you get young actors who’ve been so coached by their parents, they come on and everything’s memorized, and you have to undo that to find the quality that is their own reality,” Sullivan reflects. “Megan set a very high standard for the other young performers. By the time ‘Avonlea’ came along, I’d worked with some of the young kid performers—Zachary [Bennett, who played Felix King], Sarah [Polley, who played Sara Stanley]—and I found different qualities in each of them that had their own reality.”

Costume designer Martha Mann transported actors back in time

Sullivan first met costume designer Martha Mann at Hart House, the theater attached to University of Toronto, and was stunned by her talent and knowledge of historical dress. “She was a walking encyclopedia,” he recalls. When she began working with him on the “Anne” films, he hardly needed to suggest ideas, instead allowing her the freedom to create “this remarkable world of costumes.”

Mann constructed original costumes for the leads and sourced supporting performers’ clothing from the English company Cosprop, known at the time for supplying costumes for Merchant Ivory productions.

Mann’s passion for creating an accurate period look ran deep; she even made sure the cast wore the proper undergarments so the clothing would hang correctly. This didn’t always go over well with the cast, however. “Colleen Dewhurst absolutely refused to get into a bodice,” Sullivan recalls with amusement.

“Martha was very upset and…they had kind of a war going on about her undergarments, but that was the detail Martha put into it that made everything look and feel correct.” And it worked. The actors look as though they’ve stepped out of the early twentieth century. It was all part of creating “this very seamless look” that transports viewers whenever they revisit Avonlea.

Avonlea’s lush look and comforting view of the world

Despite this attention to accuracy, Sullivan was keenly aware that they were creating an escapist world. “They were gentlemen farmers, not real farmers, and so in that way ‘Avonlea’ really is a fantasy. It’s the way you would like the world to look, maybe not how it really looked.”

Viewers were drawn to the concept of a simpler time, especially one set before the world wars.

“I think as we approached the end of the 20th century, when ‘Avonlea’ was in its heyday, people were feeling a little bit upended, and there was something about the beginning of the 20th century that was reassuring. [Avonlea residents] were still human beings, they could be really harsh with one another, but by the same token there was a modicum of grace in it as well. People were looking for this perfect escapist world as an antidote to the world that they existed in.”

That grace and humanity still resonate all these years later. Like the last-minute scene he added to “Anne of Green Gables,” it was an unexpected development in filming that helped Sullivan find the heart of Road to Avonlea.

In the episode “Home Movie” (season 4, episode 12), an industrial magnate offers to buy up the Avonlea land to develop it into a modern town. Hetty King (Jackie Burroughs) is utterly against his proposal, and she finds an unexpected ally in Jasper Dale (R.H. Thomson), who recently filmed the Avonlea residents going about their daily lives. Hetty projects his home movie for the community and helps them realize that despite their differences, they are stronger together.

“They realized how tight-knit a community they were. Even though they could be cruel to one another, they still hung together as a community,” Sullivan says. “I realized that was partly the reason why people were coming to the series.”

“Road to Avonlea” offers a rosy glimpse of days gone by, but it also reflects the very real, very human desire for connection. And perhaps that’s why, 30 years after its premiere, viewers are still drawn to it today.

Road to Avonlea is AVAILABLE to STREAM

Road to Avonlea is AVAILABLE on DVD

Use the code WILLOWTHATCH for $10 off the Anne of Green Gables Trilogy on Gazebo TV.

Abby Murphy writes young adult books about girls discovering their strengths. A member of SCBWI and The Historical Novel Society, she is represented by Laura Crockett of Triada US Literary Agency. You can visit her blog here, where she writes about reading, writing, history, and her incurable Anglophilia.

If you enjoyed this post, wander over to The Period Films List. You’ll especially like the Best Period Dramas: Family Friendly List. Also see our our Review of Road to Avonlea, the Review of Anne of Avonlea, Introducing Anne of Green Gables, and the Family Film Roundup: American Girl Series.

Ettienne

May 21, 2020 at 1:07 pm (5 years ago)I love Road to Avonlea! Oh. So. Much. I grew up watching this series, and am still very nostalgic toward the characters. I think “Great Expectations” is my favorite episode, but “Home Movie” is a favorite too.